a

Rendering a collection, modules

Before we go into a new topic, let's go through some topics which proved difficult last year.

console.log

What's the difference between experienced JavaScript programmer and a rookie? The experienced one uses 10-100 times more console.log

Paradoxically, this seems to be true even though rookie programmers would need console.log (or any debugging method) more than experienced ones.

When something does not work, don't just guess, but log or use some other way of debugging.

NB when you use the command console.log for debugging, don't concatenate things 'the Java way' with a plus. Instead of writing

console.log('propsin arvo on' + props)separate the things to be printed with a dash:

console.log('propsin arvo on', props)If you add an object to a string, the result is a pretty useless read.

propsin arvo on [Object object]But if you use a dash you'll get the things printed to the developer-console as an object, contents of which can be read. If necessary, read more about debugging React-applications from here

Event handlers revisited

Based on last year's course, event handling has proven to be difficult. It's worth reading the revision chapter at the end of the previous part event handlers revisited if it feels like your own knowledge on the topic needs some brusing up.

Passing event handlers to the child components of the App component has raised some questions. Small revision on the topic here.

Protip: Visual Studio Code snippets

With visual studio code it's easy to create 'snippets', shortcuts to generating the most used bits of code like 'sout' on Netbeans. Instructions for creating snippets here.

Useful, ready made snippets can also be found as VS Code plugins for example here.

The most important snippet is a shortcut to adding the console.log() command, for example clog. This can be created like so:

{

"console.log": {

"prefix": "clog",

"body": [

"console.log('$1')",

],

"description": "Log output to console"

}

}JavaScript Arrays

From here on out, we will be using the functional programming methods of JavaScript array, such as find, filter and map all the time. They operate on the same general princible as streams in Java 8, which have been used last few years in ohjelmoinnin perusteet and ohjelmoinnin jatkokurssi at the department of Computer Science, and in the programming MOOC.

If functional programming with arrays feels foreign, it is worth it to watch at least the three first parts from YouTube video series Functional Programming in JavaScript:

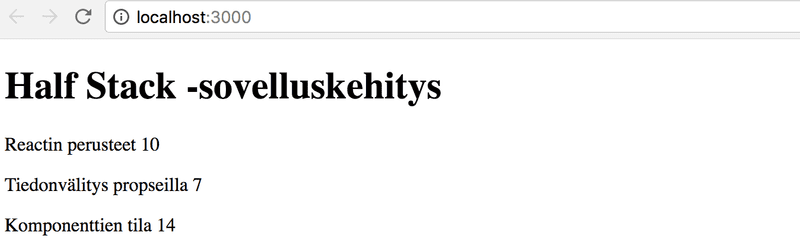

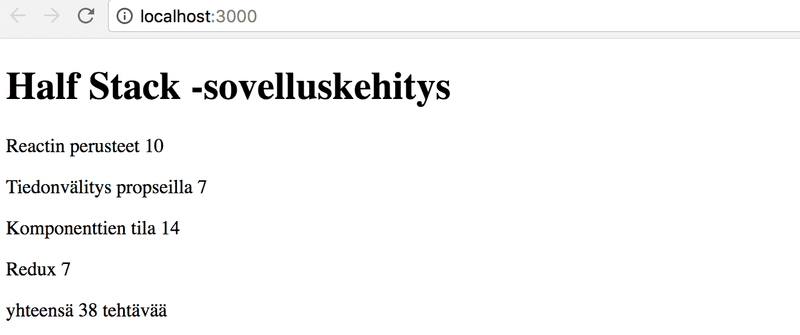

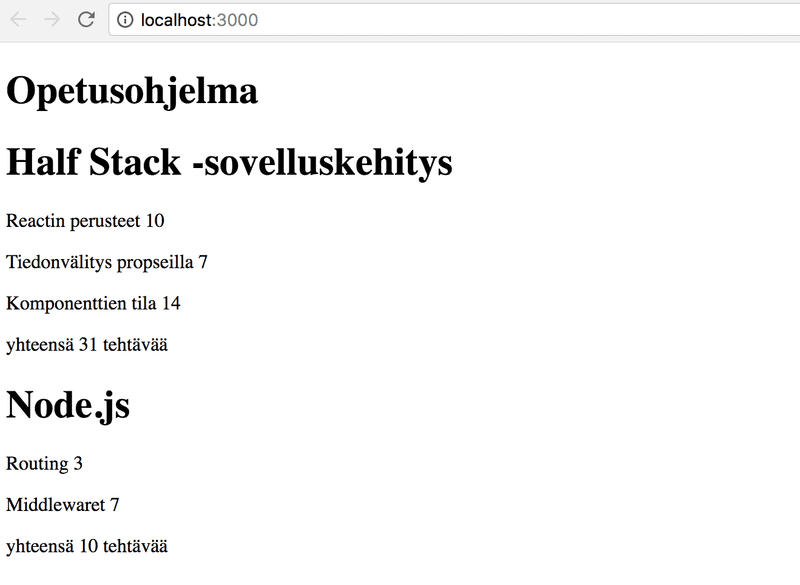

Rendering collections

We will now do the 'frontend', or the browser side application logic, in React for a similar application to the example application from part 0

Let's start with the following:

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

const notes = [

{

id: 1,

content: 'HTML on helppoa',

date: '2019-01-10T17:30:31.098Z',

important: true

},

{

id: 2,

content: 'Selain pystyy suorittamaan vain javascriptiä',

date: '2019-01-10T18:39:34.091Z',

important: false

},

{

id: 3,

content: 'HTTP-protokollan tärkeimmät metodit ovat GET ja POST',

date: '2019-01-10T19:20:14.298Z',

important: true

}

]

const App = (props) => {

const { notes } = props

return (

<div>

<h1>Muistiinpanot</h1>

<ul>

<li>{notes[0].content}</li>

<li>{notes[1].content}</li>

<li>{notes[2].content}</li>

</ul>

</div>

)

}

ReactDOM.render(

<App notes={notes} />,

document.getElementById('root')

)Every note contains its textual content and a timestamp as well as a boolean value for marking wether the note has been categorized as important or not, and a unique id.

The code is based on there being exactly three notes in the array. Single note is rendered by accessing the objects in the array by referring to a hard coded index number:

<li>{note[1].content}</li>This is of course not practical. The solution can be generalized by generating React-elements from the array objects using the map function.

notes.map(note => <li>{note.content}</li>)The result is an array of li elements.

[

'<li>HTML on helppoa</li>',

'<li>Selain pystyy suorittamaan vain javascriptiä</li>',

'<li>HTTP-protokollan tärkeimmät metodit ovat GET ja POST</li>',

]Which can then be put inside ul tags:

const App = (props) => {

const { notes } = props

return (

<div>

<h1>Muistiinpanot</h1>

<ul> {notes.map(note => <li>{note.content}</li>)} </ul> </div>

)

}Because the code generating the li tags is JavaScript, in a JSX template it must be put inside brackets like all other JavaScript code.

Often in similar situations the dynamically generated content is separated into its own method, which the JSX template calls:

const App = (props) => {

const { notes } = props

const rows = () => notes.map(note => <li>{note.content}</li>)

return (

<div>

<h1>Muistiinpanot</h1>

<ul>

{rows()} </ul>

</div>

)

}Key-attribute

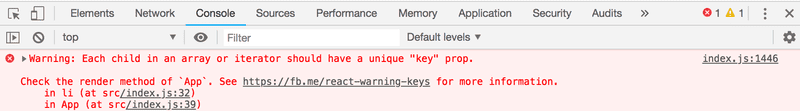

Even thought the application seems to be working, there is a nasty warning on the console:

As the page linked to in the error message tells, items in an array, so the elements generated by the map method, must have an unique key value: an attribute called key.

Lets add the keys:

const App = (props) => {

const { notes } = props

const rows = () => notes.map(note => <li key={note.id}>{note.content}</li>)

return (

<div>

<h1>Muistiinpanot</h1>

<ul>

{rows()}

</ul>

</div>

)

}And the error message dissappears.

React uses the key attributes of objects in an array to determine how to update the view generated by a component when the component is rerendered. More about this here.

Map

Understanding how the array method map works is crucial for the rest of the course.

The application contains an array called notes

const notes = [

{

id: 1,

content: 'HTML on helppoa',

date: '2017-12-10T17:30:31.098Z',

important: true,

},

{

id: 2,

content: 'Selain pystyy suorittamaan vain javascriptiä',

date: '2017-12-10T18:39:34.091Z',

important: false,

},

{

id: 3,

content: 'HTTP-protokollan tärkeimmät metodit ovat GET ja POST',

date: '2017-12-10T19:20:14.298Z',

important: true,

},

]Lets pause for a moment and examine how map works.

If the following code is added e.g to the end of the file

const result = notes.map(note => note.id)

console.log(result)[1, 2, 3] will be printed to the console. Map always creates a new array, elements of which have been created from the elements of the original array by mapping using the function given as a parameter to the map method.

The function is

note => note.idWhich is an arrow function written in a compact form. The full form would be:

(note) => {

return note.id

}The function gets a note object as a parameter, and returns the value of it's id field.

Changing the command to:

const result = notes.map(note => note.content)results into an array containing the contents of the notes.

This is already pretty close to the React code we used:

notes.map(note => <li key={note.id}>{note.content}</li>)which generates a li tag containing the contents of the note from each note object.

Because the function parameter of the map method

note => <li key={note.id}>{note.content}</li>is used to create view elements, the value of the variable must be rendered inside of curly brackets. Try what happens if the brackets are removed.

The use of curly brackets will cause some headache in the beginning, but you will get used to them soon. The visual feedback from React is immediate.

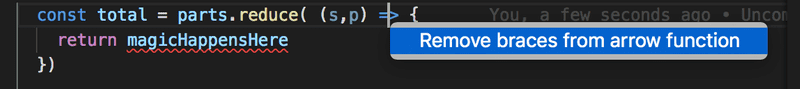

Let's examine one source of bugs. Add the following to your code

const result = notes.map(note => {note.content} )

console.log(result)It will print

[undefined, undefined, undefined]Whats the matter? The code is exactly the same as the one that worked earlier. Except not quite. The map method now has the following function as a parameter

note => {

note.content

}Because the function now forms a code block, it's return value is undefined. Arrow functions return the value of their only statement only if the function is defined in the compact form. Without the code block:

note => note.contentNote that 'oneliner' arrow functions do not need to be, nor should always be, written on one line.

Better formatting for the helper function returning the rows of notes in our application could be the following version spread over multiple lines:

const rows = () => notes.map(note =>

<li key={note.id}>

{note.content}

</li>

)This still is an arrow function with only one statement, the statement just happens to be a bit more complicated.

Antipattern: arrow indexes as keys

We could have made the error message on our console dissappear by using the array indexes as keys. The indexes can be retrieved by giving a second parameter to the map-method:

notes.map((note, i) => ...)When called like this, i gets the value of the index of the position in the array where the Note resides.

So one way to define the row generation without getting errors is

const rows = () => notes.map((note, i) =>

<li key={i}>

{note.content}

</li>

)This is however not recommended and can cause bad problems even if it seems to be working just fine. Read more from here.

Refactoring modules

Let's tidy the code up a bit. We are only interested in the field notes of the props, so let's receive that straight using destructuring:

const App = ({ notes }) => { // ...

return (

<div>

<h1>Muistiinpanot</h1>

<ul>

{rows()}

</ul>

</div>

)

}If you have forgotten what destructuring means and how it works, revise this.

We'll separate displaying a single note into it's own component Note:

const Note = ({ note }) => { return ( <li>{note.content}</li> )}

const App = ({ notes }) => {

const rows = () => notes.map(note =>

<Note key={note.id} note={note} /> )

return (

<div>

<h1>Muistiinpanot</h1>

<ul>

{rows()}

</ul>

</div>

)

}Note, that the key attribute must now be defined for the Note components, and not for the li tags like before.

A whole React application can be written to a single file, but that is of course not very practical. Common practice is to declare each component in their own file as a ES6-module.

We have been using modules the whole time. The first few lines of a file

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'Import two modules, enabling them to be used in the code. The react module is placed into a variable called React and react-dom to variable ReactDOM.

Let's move our Note component into it's own module.

In smaller applications components are usually placed in a directory called components , which is placed within the src directory. The convention is to name the file after the component.

Now we'll create a directory called components to our application and place a file Note.js there. The contents of the Note.js file are as follows:

import React from 'react'

const Note = ({ note }) => {

return (

<li>{note.content}</li>

)

}

export default NoteBecause this is a React-component, we must import React.

The last line of the module exports the declared module, the variable Note.

Now the file using the component, index.js, can import the module:

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

import Note from './components/Note'

const App = ({notes}) => {

// ...

}The component exported by the module is now available for use in the variable Note just as it was earlier.

Note, that when importing our own components their location must be given in relation to the importing file:

'./components/Note'The period in the beginning refers to the current directory, so the module's location is a file called Note.js in a subdirectory of the current directory called components. The filename extension can be left out.

App is a component as well, so let's declare it in it's own module as well. Because it is the root component of the application, we'll place it in the src directory. The contents of the file are as follows:

import React from 'react'

import Note from './components/Note'

const App = ({ notes }) => {

const rows = () => notes.map(note =>

<Note

key={note.id}

note={note}

/>

)

return (

<div>

<h1>Muistiinpanot</h1>

<ul>

{rows()}

</ul>

</div>

)

}

export default AppWhat's left in the index.js file is:

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

import App from './App'

const notes = [

// ...

]

ReactDOM.render(

<App notes={notes} />,

document.getElementById('root')

)Modules have plenty of other uses than enabling component declarations to be separated into their own files. We will get back into them later in this course.

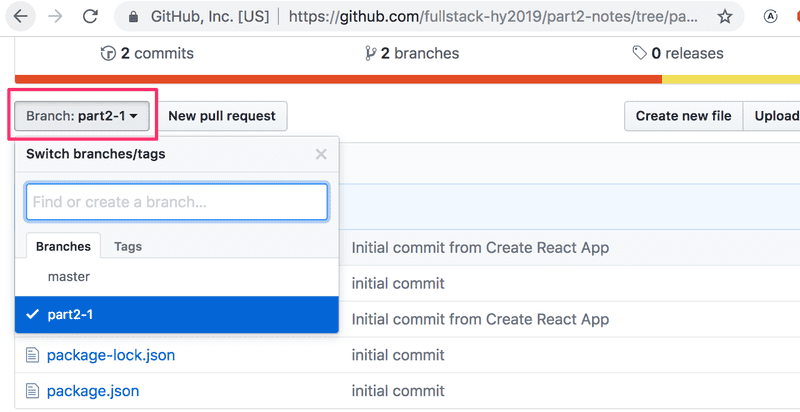

The current code of the application can be found from github.

Note, that the master branch of the repository contains the code for a later version of the application. The current code is in the branch part2-1:

If you clone the project to yourself, run the command npm install before starting the application with npm start.

When the application breaks

When you start your programming career (and even after 30 years of coding like yours truly) quite often the application just breaks down completely. Especially this happens with dynamically typed languages like JavaScript, where the compiler does not check the data type of e.g function variables or return values.

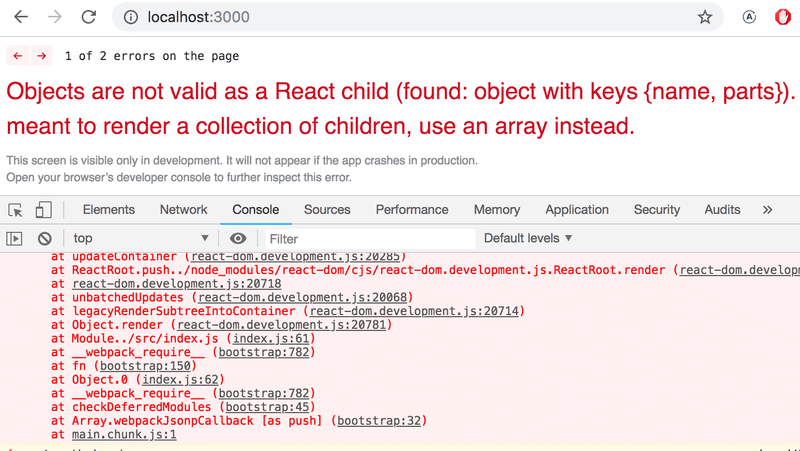

React explosion can for example look like this:

In these situations your best way out is the console.log. The piece of code causing the explosion is this:

const Course = ({ course }) => (

<div>

<Header course={course} />

</div>

)

const App = () => {

const course = {

// ...

}

return (

<div>

<Course course={course} />

</div>

)

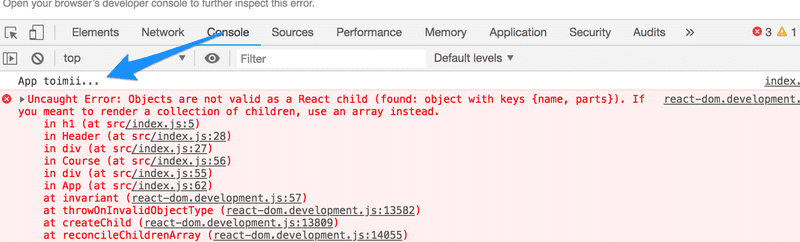

}We'll hone in on the reason of the breakdown by adding console.log commands to the code. Because the first thing to be rendered is the App component, it's worth putting the first console.log there:

const App = () => {

const course = {

// ...

}

console.log('App toimii...')

return (

// ..

)

}To see the printing on the console we must scroll up over the long red wall of errors.

When one thing is found to be working, it's time to log deeper. If the component has been declared as a single statement, or a function without a return, it makes printing to the console harder.

const Course = ({ course }) => (

<div>

<Header course={course} />

</div>

)The component should be changed to the longer form, so we can add the printing:

const Course = ({ course }) => {

console.log(course) return (

<div>

<Header course={course} />

</div>

)

}Very often the root of the problem is, that the props are expected to be different type or called different than they actually are, and desctructuring fails. The problem often begins to solve itself when desctructuring is removed and we see what the props actually contains.

const Course = (props) => { console.log(props) const { course } = props

return (

<div>

<Header course={course} />

</div>

)

}If the problem has still not been solved, doesn't help but continue tracking down the issue by writing more console.log.

I added this chapter to the material after the model answer of the next question exploded completely (due to props of the wrong type), and I had to debug by using console.log.